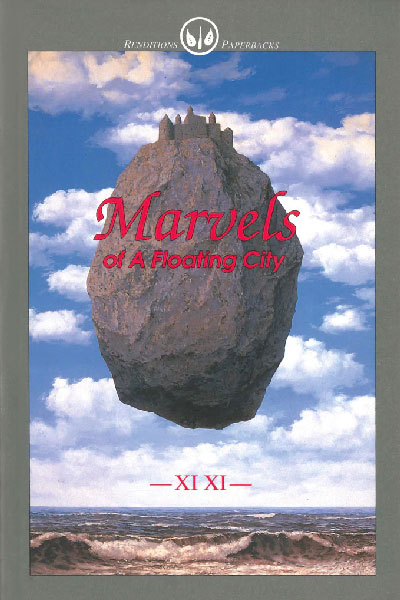

The Merry Building

Xi Xi has described her ground-breaking novels from the 1970s, My City and The Merry Building, as “two ways of writing the same place.” While My City draws on perspectives from flaneurs, the Merry Building is set in a 12-floor residential building. If the city’s development is a product of imperialism, governed not only by colonizers but what Paul Virilio regards as the “rule of speed,” then Xi Xi instead uses her technique of “slowness” to record the energy of the daily lives of everyday people. As compared to the younger, more “local” perspective of My City, The Merry Building pays special attention to the immigrants of Hong Kong who come from different backgrounds. Instead of a single hero, here are the “strangers” who play the role of the main characters. The Merry Building portrays public spaces invented spontaneously by these inhabitants.

We’ve selected an excerpt from chapter 6 to share with you here. Right after the lift in the building breaks, the residents encounter each other much more in the public spaces, e.g. the staircase and ground floor. Xi Xi writes in minute detail about their body movements, dialogues, and material life, showcasing a slice of life drawn from a variety of inhabitants in the city, from children to the elderly, from humans to animals.

The Merry Building

Chapter 6 (excerpt) translated by Andrea Lingenfelter

Entering the building manager’s office, you come face to face with the owner of Hing’s and exchange nodded greetings. The office is a lot more crowded than it used to be. There’s a wooden cart leaning against one of the walls, and if you look closely, you’ll see traces of burnt charcoal on the cart, which you’ll then recognize as belonging to the woman who sells noodles. Ever since the elevator broke down, it wasn’t clear how she could bring it downstairs, so she never took it back up. Instead, each morning she retrieves it from its place by the wall and pushes it outside, returning it to the same spot in the afternoon. The bulk of the cart cuts off half of the picture on the TV, and often there’s nothing but one eye and half a mouth flickering on the screen. The thick and solid human wall no longer appears in front of the elevator, and the bodies that used to be inert as stones have been transformed into a moving river. Threading through the narrow, snaking passage, this human river almost never ceases flowing, as people come and go, passing each other on their way to and from the stairwell. Sometimes, a couple of people will bump into each other in the corridor, and each will simultaneously try to step into the same spot, until, after several rounds, they’ll break apart. But usually the crowd follows certain rules, with people keeping to the wall or to the banister and proceeding in single file. Sometimes, somebody will come tromping down the stairs all by themselves, free and easy, and at other times, a whole bunch of people come marching down like a platoon, with the little kids hopping and skipping and the elderly taking tentative and unsteady steps. Meanwhile, those climbing the stairs wear pained expressions and furrowed brows. You follow the owner of Hing’s up the stairs, like an ant among legions busily foraging for food.

The elevator has been broken for many days, and it has absolutely nothing to do with the electrical supply. People would open the elevator doors and hoisted up to the top floor, dragging large machines inside. They tried to fix it many times, but it’s still no use. Word is that it needs a major overhaul: rust removal, replacement of the cables, and rewiring. When you’re climbing the stairs, you can hear the sound of tapping on the other side of the wall, interspersed with earsplitting bursts from an electric drill. The stairwell is unlit, and almost everyone carries a flashlight, and anybody who doesn’t bring their own source of illumination tags along with others when traversing the dark pumping room. At each floor, groups of people are either peeling off from or attaching themselves to the gaggle, in a constant turnover of old and new. In just a few days, the stairs have grown visibly soiled, the walls sport fresh dings and marks, and the landings are littered with the melonseeds shells and torn red envelopes, and the odd dried out peach twig. Because of the large number of people, as a matter of course, those using the stairway have naturally divided themselves into two groups: the handrail side is for people going up, and the wall side is for the other direction. The people heading up with you advance at a relatively leisurely pace, and you can’t see all the way to the front of the line. All you know is that someone very tall is fishing out a packet of cigarettes, pulling out what seems to be the last one, crumpling up the pack and dropping it on the ground before he takes out a match and, turning his massive block of a body sideways till it all but fills the passageway like a giant tree, with a scritch and a scratch the match flares and he lights the cigarette. During this pause, the people behind the smoker are stuck and have to entertain themselves, while some of those in front of him are able to expand their lead. In these newly divided ranks, the smoker becomes a line leader, but all you can see is him exhaling cloud of smoke and tossing the match into a corner of the stairs. Those who pass by a little later can still see the twinkling gold sparkles and curling black smoke. Directly behind this man is a woman with her sleeves rolled up to her upper arms, dragging a gigantic plastic bag with both hands. In the gloom, you can just make out what looks like a ball of twine as gold as straw, and it seems the bag is filled with hundreds of squished up wigs. Despite the massive bulk of the plastic bag, the woman doesn’t seem to be finding it that arduous, and it bounces up the stairs behind her like a bundle of kapok. Right on the woman’s heels is a pair of children about ten years old, and each is carrying a smallish plastic bag, one filled with the heads of plastic toys, which can be snapped on to the necks of other toys. The heads are all bald, with molded noses and mouths, and inset eyes that can roll around and open and close, and because they’ve been thrown into the bag willy-nilly, the heads bump around together, and the eyes keep getting jostled, so that some move out of place and show only the whites, while others are out from the corners of the eyes and seemed to give you the side eye. The other child’s bag is filled with plastic body parts, nothing but hands and feet, and each hand is exactly like the others, the same color, shape, size, and length. The children are goofing off as they walk, blowing white bubbles that explode with a pop, before they flip the empty husk back into their mouths and chew some more.

When I finish making this bag of dolls, I’ll have two dollars.

I have more than you do. I’ll have two and a half dollars.

I’m gonna buy a water pistol.

I’m gonna buy a plush toy snake so I can scare the kids at school.

I think there’s an English quiz tomorrow.

So what? So you get another zero, what’s the big deal?

Right behind the kids is the owner of Hing’s, with a cylinder of LPG slung over one shoulder and stabilized with a hand, while the other hand grips two flat cylindrical canisters, and when his hand swings back and forth like a pendulum, you can see a fish painted on the sides of the canisters. You have no idea how many people altogether are behind you, but you can hear the sound of an endless stream of footsteps, and at a turn in the stairwell, you spot an old man delivering food from a small eatery with a pot metal box in his arms, and after him are two young women, both wearing vertiginously high platform shoes that look like flat irons and make them teeter like stilt walkers with each step. After passing the pumping room, the stairwell brightens, and some people on the landing cut into the line of people that snakes like a dragon, and one of them someone is carrying a bundle of padded jackets, which makes them look like a circus juggler. At the third floor, a powerfully built man halts the crowd, and whether they’re heading up or down the stairs, they are all ushered into the corner, where they stand pressed together shoulder to shoulder.

Sorry, sorry, this won’t take long.

As long as you’re not planning to rob me!

A middle-aged man standing in the stairwell shouts up to the next floor, and then you hear a loud rumbling, as cloth sacks come tumbling one by one down the stairs. One of sacks is transparent enough that you can see there are balls of yarn and bobbins inside, and at all at once a dozen more sacks like this come bouncing down, and the people below quickly kick and push and drag them into a heap beside the stairs. Someone else comes running down the stairs and reaches out to do something, while yet another person comes carrying little folding metal pushcart, the handles folded back against its checkered sides. While the transporting the balls of yarn apologize nonstop, some members of the crowd are ready to jostle and shove their way up or downstairs again, but others take the opportunity to catch their breath. Of those coming up from the ground floor, the last to arrive are the first to set out again, and the old man holding the take-out boxes continues to carefully pick his way upstairs. The child carrying the pieces of plastic toys sets the bag down on a step and starts to push and roll it, but after about five stairs, he picks it up again, and walks on properly, a big, white bubble emerging from his mouth like a pearl. A married couple shifts burdens in their hands at this way station, the young wife passing the baby she’s been holding to her husband, along with the shawl it’s been wrapped in, while simultaneously taking the carryall her husband was holding, the bag so overstuffed the zipper won’t close, exposing a cash of bottles and folded diapers. The baby is sound asleep doesn’t wake up even as its past from hand to hand, and the mother reaches to straighten out and tuck in the baby’s blanket, peeling back the cloth covering the baby’s face, before continuing to climb the stairs along with her husband. After this time out, the stairwell starts to bustle again, with some people still stuck in the corners of the landings and those descending the stairs filling the stairwell with noise, like a team of horses speeding to market.

Hey—Mr Hing, since you’re around, could you deliver a can of kerosene upstairs for us? And a half dozen eggs.

If you don’t need them right away, how about tomorrow?

Okay, tomorrow then! Do you remember where I live? Twelfth floor, Block 2.

The owner of Hing’s picks up the oil can he’s set down, and, with a great show of lifting something very heavy, he hoists it to his shoulder, which now has a layer of white plaster stuck to it. You’re still right behind him, and in front of him are the two women in vertiginous platforms, who are now discussing whether or not to buy a pair of high-heeled boots and how on TV they’ve seen women who are très chic and au courant dressed in the newest ever-changing fashions, and lately, everyone who wants to stay in style is rolling bulky jeans up to their knees. One of the women asks her friend for her opinion about her plans to switch to a swimsuit in European colors when summer arrives.

At the fourth floor, the women exit the stairway. Before long, and you don’t know if it’s because the people behind you have picked up the pace or if the people in front of you have slowed down, but the owner of Hing’s is close behind the women. You can even hear the heads of the family talking about household expenses, rising costs, and monthly shortfalls, and you can hear the footsteps of the woman of the house becoming increasingly heavy. Whenever someone coming down the stairs knows the owner of Hing’s, they nod and say hello, hailing him like a hard-working delivery truck. He ducks his head as he replies, as if exchanging more words might put him on the hook for yet another delivery. Soon, he’s moved the gas cylinder to block his line of sight, so that he doesn’t have to meet anyone’s eyes, all the while complaining bitterly to himself like a soloist belting out his theme song.

Business seems to be booming, and indeed, Hing’s is living up to its name, which means “prospering”, with Jane Doe ordering a can of kerosene and Joe Blow wanting a canister of LPG, but what they really want is to find a delivery person so they won’t have to drag themselves downstairs to buy in person. The orders for kerosene and LPG are a ruse, but the orders for canned goods, eggs, paper goods, and packaged noodles are genuine. It’s been cold out, but some folks are buying six packs of soft drinks, and while they’re at it they order a couple preserved eggs, three cans of lunchmeat, a dollar’s worth of pickled tubers, fifty cents worth of rice noodles, a tin of anchovies, a can of corn, two cans of green peas, two catties of unrefined slab cane sugar, a half catty of red beans—all the fixings for dinner and a midnight snack. On a normal day, delivering food was a hassle, but he could manage; but now that the elevator was broken, how was he supposed to keep up with all this business? And the higher the apartment, the more often they called—A packet of noodles and some savory-sour sauce—for the 11th floor! Fancy Tsaimei rice and oyster sauce!—Twelfth floor! You never saw anyone on the second floor ordering rice or oil.

Hey, Mr. Hing! Are you still making deliveries yourself?

I’m afraid so! We’re in the same boat.

What’s going on with your building? The elevator’s been broken for ages and it still hasn’t been fixed, and I have to spend the whole day running up and down the stairs. I can leave the mailbag in the office, but this building is over ten stories tall, and if you have a registered letter, I have to climb hundreds of stairs, and if the person it’s addressed to doesn’t happen to be home and nobody else on that floor bothers to answer their door, I have to come back and slog up the stairs all over again the next day. With this delivery system, I wish every month was December, because at least we get a subsidy in December. Lately I’ve had to pay out-of-pocket to replace my worn-out shoes.

The owner of Hing’s and the postal worker brush past each other, the one in front pressing his lips together and holding his tongue, the one behind muttering away like a monk chanting sutras, a schoolboy reciting his lessons aloud, or a samurai without a master wandering and ranting alone. After two more flights, a small contingent takes a rest on the landing, and the owner of Hing’s steps towards the clump of people and unshoulders his burdens for a moment. The soreness in your legs suddenly intensifies, and, following in the footsteps of those ahead of you, you stop in the corner. After a brief rest, a few people peel away from beside you, and you stand in the notch at the landing while two streams of people filled the stairwell. You observe these motley troops, their brooding silence harboring impatience and distress, each and every face reflecting the utter exhaustion dwelling in each heart. You have never seen so many heads and faces in one place, and while none of the arrangements of features are unfamiliar—you might’ve noticed them in the elevator in the past or seen them in the crowd in the building office—with the exception of the fresh faces of the children, which still retained their cheerfulness, most of people’s expressions tended towards the glum. Now that you have to rely on your own two feet to get around, you’ve discovered the cumbersomeness of the burden each person must bear. Over half of the people have something, over half of the people are carrying things in their hands, or maybe there cradling something in their arms that they can’t throw away; one person is shouldering several dozen stocks of red-skinned sugarcane, and even though he tries hard to judge the length of this load each time he approaches turn in the stairs, dark mud from the canes keeps leaving smears on the walls. A person coming up from downstairs seems to be doing a dance with a pair of extraordinarily long bamboo clothes drying poles capped with rubber sleeves, one red and one green, and as he walks with the tips of the polls waving in the space overhead, he can’t help scraping plaster from the ceiling and leaving bits of it scattered all over the floor. The woman who is just now coming around the corner has to fan the dust away from her face with her hand while at the same time brushing it off of her hair and placket. The person behind is using both hands to carry a large bowl covered with a saucer, and on top of the saucer is a small container of soy sauce that now has little chunks of plaster floating in it and is obviously no longer usable. The man hoisting the bamboo poles is big and burly, with imposing but disagreeable features, and the person who bringing that the food downstairs doesn’t say a word and passes by the man in silence. Instead, it’s the plump woman following close behind the large, muscular fellow with the bamboo who shouts out: Hey! Why don’t you just knock the whole place down! She is carrying a plastic buckets and metal pots brimming with greasy bowls and chopsticks, which clatter as they swing back and forth with every step she takes. At the jog in the stairs, she and several people standing there call out their greetings in unison, and you recognize her as the woman who rises with the sun to sell the noodles used to be inside the metal pots and have now all been sold.

There sure are a lot of people standing here. It looks like you can’t take another step either, Mr. Hing.

I’ve run out of gas.

Are you sure about that? What’s in that cylinder?

The noodle-seller takes one of the metal pots and places it on the neck of the LPG cylinder, and seeing that it isn’t stable at all, she sets the pot on the ground, grinning all the while. She’s the only adult you’ve seen in this entire building who still has a sense of humor. It is at this moment that a plastic bathtub makes a sudden appearance in the stairwell. Carried by two people who don’t seem to be exerting much effort, this sight attracts countless pairs of eyes, like the Southern Cross twinkling on the horizon. The bathtub gives off a faint blue glow, and as it passes the window openings and is in full sun, it’s translucent like a bar of impurity-free neutral soap. They’ve turned the bathtub on its side to move it forward, and people can see a drain hole on the bottom of the tub and a silver chain dangling from the side wall, with a round rubber stopper that swings like a pendulum.

That’s a bathtub, isn’t it?

Yep, just on the market.

Can you put hot water in it? Can it hold a person who weighs 200 pounds? Can you take bubble baths in it? How do you drain the water? There’s no way you can get it into the bathroom, is there? When we bought a refrigerator, even though it only had a single door, we still had to take off the kitchen door to get it inside.

How much did you pay for it? Where did you buy it? Does it come in other colors? Like pink? Is this the smallest size? It looks really lightweight—is it hard plastic? You see something new every day! Is it imported?

Too bad there’s no faucet. Installing a hot water heater is expensive, isn’t it? Is it dangerous to use a hot water heater? If you use a showerhead, can’t you save a lot of money?

What a great place to wash clothes!

Most of the crowd in the stairwell follow the bathtub, and this novel source of excitement makes them forget their fatigue, at least for a while, and gives them something new to talk about. Some people debate the relative merits of gas versus electricity, while others engage in a point by point comparison of the importance of bathtubs as opposed to televisions, and a whole slew of children have followed the bathtub to its final destination, where they take careful note of its final disposition. The woman who sells noodles emerges from the stairway with a bag of fresh sesame oil noodles and another bag filled with green and white two-toned bean sprouts, and she hands these plastic bags from the market to her mother, then turns, scoops up the metal pots and plastic buckets, and heads towards the corridor with her mother. The two women briefly step aside, seeing the elderly manager sweeping up pile of rubbish and resting with the long broom handle in hand.

End of Excerpt

*

*

*

*

Three Texts by XiXi

Find a list of useful links to websites, databases and scholarly articles related to Xi Xi’s literary works.

Since November 2021, we have organized various writing workshops both online and in person, in areas such as Sham Shui Po, Wan Chai, Kowloon Tong, etc. Learn more about these workshops.

©2025 - All rights Reserved. Our Xi Xi Our City.