Mourning a Breast

After being diagnosed with breast cancer in 1989, Xi Xi published a series of related works, which were collected in the book Elegy for a Breast in 1992. Elegy for a Breast is not a traditional memoir that draws mainly on personal experiences and feelings, but rather it is a juxtaposition of various type of writing styles, involving knowledge of medicine, translation, architecture, etc. The critic Ho Fuk Yan called it a “new style” akin to “a kaleidoscope”, while William Tay regard it as “a novel of mixed genres” or “a comprehensive narrative style of multiple genres”. In addition to its formal breakthrough, Elegy for a Breast is also a kind of experimental life writing, reflecting on the relationship between the city and its citizens through the eyes of a patient. It not only affirms the importance of the unique experience of each individual, but it also considers how systems in the city can be more humane and responsive to human needs.

We’ve selected a chapter called “Bathroom” to share with you here. In this chapter, Xi Xi writes about how she redesigns her apartment to create her dream bathroom. Her experience with the bathroom, however, changed significantly before and after her illness. Xi Xi was fully aware that the beauty of a place does not really have an objective standard but is constantly changing due to the unique needs and feelings of its user. This principle can be applied to private residences as well as urban buildings. A building is not necessarily good or bad because of its appearance, but whether it can be designed with people’s needs in mind. At the end of the piece, Xi Xi specifically mentioned the Cultural Center that was just completed in Hong Kong at the time. In response to the unfavorable comments about the appearance of the building, such as “it looks just like a bathroom,” Xi Xi writes, “at different times, in different places, we feel differently about the bathroom.”

The Bathroom

Excerpt from Xi Xi, Mourning a Breast (translated by Jennifer Feeley)

I hadn’t properly bathed in half a month. Fortunately, it was September, and the weather was cooling off. Instead of bathing like usual, I could only take half-baths, dabbing my upper body with a damp washcloth.

A week after coming home from the hospital post-op, I went to the clinic to have the surgeon remove my stitches. I didn’t know why he hadn’t stitched up my wound with fishing line, which wouldn’t have needed to be taken out—the line could’ve remained in the wound, gradually dissolving over time. For patients, so many things are unclear, and no one gives us a choice; we’re like helpless little lambs. For all I knew, the surgeon could’ve used sheep intestines, thick and black, reminiscent of beef tendons. Lying back on the exam table, I felt the doctor tear open the large bandage on my chest, removing the stitches with scissors, the sound crystal-clear, a clean and neat snip, snip.

How many stitches? I asked.

Twenty-five, he replied.

Twenty-five stitches—that’s a long centipede. I remember falling and injuring my head in school when I was a child. The school doctor immediately stopped the bleeding and stitched up the wound. By the time my mother arrived, my head was all bandaged up so that I looked like an Indian person in a turban. Back then, when blood streamed down my face, I rested at home for a month before returning to school, and I only had three stitches in the back of my head. Now I had twenty-five stitches. I couldn’t bring myself to think about it.

The incision was long, and the stitches were removed over the course of two sittings. The first time, every other stitch was snipped with scissors, the short pieces of thread like severed parts of an earthworm. In fact, the wound had already closed, the tissue connecting skin to skin—even if the stitches had been removed all at once, the wound wouldn’t have split open. But the doctor was cautious, which made feel more at ease.

A few days later, I went back to the clinic a second time, and the large bandage on my chest was torn open again, the remaining stitches snipped one after the other, as though I were a shoe, and the doctor a shoemaker. All of the stitches were removed. This time, the doctor no longer applied a large, wide bandage over the incision; instead, he crisscrossed the wound with strip after strip of narrow bandages, resembling a double-gated door sealed shut with strips of paper, a practice employed in imperial China when the occupants of the house had offended someone from the government. During this visit, the doctor informed me that I could shower when I got home. The water would naturally loosen the small seals on the wound, so they wouldn’t need to be ripped off.

Finally, I could shower! I could stand my entire body beneath the shower head, the water flowing over me. The most relaxing part was washing my hair—I no longer had to bend over and bury my head in the sink. In fact, I couldn’t easily lift my right hand above my head, so I hadn’t been able to give myself a haircut. After I got home, I took several showers, but the small bandages didn’t loosen. I left them on until a few days later, when one by one they fell like yellow leaves from a tree, and the shackles of my wound were lifted completely.

I loved the bathroom in my family’s home. It was our family’s favorite place. We paid for our flat in installments—because we weren’t rich, we could only choose a small unit, comprised of one large room, a kitchen, and a bathroom. The bathroom was like an elevator car, with only a toilet and tiny sink inside. We’d bathe using the handheld shower head that hung on the wall. I worried every time I used it. There was nowhere to place my dry clothes, and I even had to hide the toilet paper. Of course, it was cold water that sprayed out. After showering, the toilet, sink, walls, and door panel would all be wet, and the water on the floor, unable to drain quickly enough, would overflow outside the door. Taking a shower, followed by the grueling cleanup of wiping the walls, wiping the door, wiping the toilet lid, and mopping the floor, was hard work. We bathed in order to clean ourselves, but the labor afterwards left us covered in stinky sweat from head to toe. When it was cold, we had to boil water in order to bathe, but there was no place to set down the water pot—who could sing in such a bathroom?

Your home didn’t have a bathtub either? she asked.

Our home didn’t have a bathtub either, I said.

I was on the phone with my friend who loves cats, chatting about everything under the sun. We began discussing bathtubs. Nobody had one. I could only sigh—I certainly had a fair number of poor friends. Half a year later, she called to tell me she now had a bathtub. Necessity is the mother of invention. Be inventive. Just move the wall between the bathroom and the kitchen, and voilà, problem solved. I understood at once.

My kitchen was exactly twice the size of the bathroom and could accommodate a refrigerator and tabletop sewing machine. The truth was, I didn’t need such a spacious kitchen. And so, I pulled out a ruler, measured from left to right, drafted designs for a week, then hired a mason to come do renovations. A wall torn down, a wall built, a drain chiseled, electrical lines installed, water pipes laid, sand and gravel flying everywhere—at long last, the bathroom was constructed. The small kitchen seemed even better than before, as it was outfitted with tidy cupboards that stored all of the clutter. Only kitchen appliances such as an electric rice cooker, an LPG cooktop, and water boiler remained on the counter. Of course, the refrigerator was moved to the dining room, and the old sewing machine was so outdated that I simply gave it to my neighbor.

I didn’t expect the remodeled bathroom to be so satisfying. A three-piece ivory-colored bathroom set, exceptionally pleasing to the eye, the floor inlaid with I-shaped umber chamotte bricks, the walls covered in subtly patterned square white tiles that stretched from the floor to the ceiling. The bathtub was low and wide, equipped with an electric water heater—bathing was now truly a treat.

It was just a week of dust and banging, just two days of having to use the neighbor’s bathroom, and then all the disruptions and racket were over. The bathroom not only had space for a washing machine but also a portable radio. A towel hung from the tiled wall, and a huge mirror was affixed above the sink. There was a louvered door, two large windows, and a built-in cupboard with pill bottles, makeup, shampoo, and soap hidden inside. When friends dropped by to see it, they all oohed and aahed in surprise. What a lovely bathroom! It was lovely because the proportions didn’t match the rest of the unit—just like a shabby hut in the countryside, the flat seemed like it should’ve been fitted with a latrine. However, shouldn’t a person’s most essential, most comfortable living space be the bathroom?

I phoned my friend who loves cats and Peanuts comics and told her, “I have a bathtub at home, too.” We both felt incomparably happy. She came to my place to have a look—in fact, I’d also gone to her home to check things out. Who’d have thought we’d end up fussing over such silly things? Strangely enough, the bathroom doubled in size, but the kitchen didn’t look small. Three or so people could stand inside smiling without feeling crowded.

I loved the bathroom so much that I often brought in a small stool and read books while listening to classical music on Radio 4. In no time, I’d be soaking in a tub overflowing with sweet-smelling bubbles—indeed, this was the golden age of stretching out and cleansing my body. Lying back in the bathtub was so comfortable, Mozart’s piano concertos flowing like pearls, seahorse bath salts smelling like waves, an old book telling a faded and far-off story.

All the joy in the bathroom had gone. Now, I was so repulsed by the bathroom that I no longer took bubble baths, nor did I linger inside reading books and listening to music. Each time I showered, I just stood beneath the shower head and took a quick shower, then dried off, got dressed, and distanced myself from the battlefield like a deserter. The bathroom had become my battlefield, and I struggled to escape my body as though I were escaping a terrifying ghost.

At last, I had to confront reality. The small bandages that acted as seals had loosened and fallen off, revealing the shape of my wound. Looking down, I saw a long scar on my chest, calling to mind a railroad zigzagging through a country field. I held out my hand to compare; it was precisely the length of my palm. I suddenly remembered making a zipper for a skirt back when I used to sew clothing—it was that long.

A man who’d had a breast tumor was interviewed on the TV news. He was in his fifties. Perhaps because he was a manly man, when he bared his chest to the camera lens, I only saw a horizontal incision across his chest. Nothing else was different. It was the equivalent of seeing other people’s scars from an appendectomy or Caesarian section—it didn’t shock me at all. Men don’t have bulging breasts. He reminded me of a wounded soldier who’d been on the battlefield.

I thought I was in the same situation as the man on TV, only I had a zipper-length incision, but no, that wasn’t the case. The scar on my body was oblique, sloping at a 45-degree angle from the side of my ribs up to my chest, spanning several ribs. The entire breast was missing. The entire breast, including the nipple, areola, mammary gland, and large amounts of fat and connective tissue.

The structural unit of the middle gland of the breast has been compared to a peach tree in March. The cystic lobules formed by glandular tissue and the mammary lobules are like clusters of blooming peach blossoms, and the glandular cells where milk is produced are like petals. Milk flows from peach-blossom-like glandular tissue into branch-like mammary ducts, and is then funneled into trunk-like lactiferous ducts. Each breast has fifteen to twenty cystic lobules and a corresponding number of lactiferous ducts arranged in a radial pattern in the center of the nipple.

The peach-tree-like glandular tissue is, of course, the main structure of the breast, but it’s only a small percentage of the overall volume of the breast. The contour of the breast is mainly composed of fat and connective tissue, including Cooper’s ligaments. The peach tree that had been on my body, along with the soil around it, was missing. If my right breast was once a hill, it was now a sunken valley; if it was once a pale and delicate bun on a plate, now all that was left was an empty plate. I quickly got dressed then rushed out of the bathroom.

How did the eighteenth-century French count, Georges-Louis Leclerc, Comte de Buffon, put it? There are three types of monsters who can be distinguished from humans: the first type is a monster formed by an excess of organs; the second type is a monster formed by a lack of organs; the third type is a monster formed by an inversion or misplacement of organs.

There are so many monsters in the world: nine-headed birds, two-headed snakes, the three-eyed deity Huaguang, the thousand-armed Buddha—all of them are monsters. If you flip through the pages of the Classic of Mountains and Seas, Investiture of the Gods, and Journey to the West, they’re full of all sorts of monsters.

*

“Heavenly Questions” from the Songs of Chu asks: “Where does the mighty nine-headed snake slither to and fro?” The snake in question was a large, venomous snake with nine heads. This was a monster formed by an excess of organs.

*

Discourses Weighed in the Balance reads: “There is a three-legged raven in the sun.” When the legendary archer Hou Yi shot at the suns, he shot down nine of them, and thus nine three-legged ravens died. This mythical bird in the sun had three legs. This was a monster formed by an excess of organs.

*

“Classic of Western Regions Beyond the Seas” from the Classic of Mountain and Seas reads: “The Land of the One-Armed People is located north of the Land of the Three-Bodied People. There they have one arm, one eye, and one nostril.” The people in this country only had one arm, one eye, and one nostril. They were monsters formed by a lack of organs.

*

Chapter Six from A Garden of Anomalies reads: “During the Yuanjia reign of the Liu Song dynasty, a one-legged ghost suddenly appeared to Song Ji of Yingchuan in the daylight. It was about three feet tall.” As there are one-legged people, certainly there are one-legged ghosts. A one-legged ghost is a monster formed by a lack of organs.

*

“Basic Annals of the Three Sovereigns,” the supplement to the Records of the Grand Historian, reads: “One with a snake’s body and a human head has the virtue of a sage.” Fuxi was said to be the son of the God of Thunder. Studying how spiders wove webs, he built a ladder to scale the heavens. With a human head and snake’s body, Fuxi was of course a monster formed by an inversion or misplacement of organs.

*

“Classic of Western Regions Beyond the Seas” from the Classic of Mountain and Seas reads: “The deity Xingtian came here and fought with the Supreme God to see who had greater spiritual powers. The Supreme God cut off his head and buried it on Mount Changyang. Thereupon, Xingtian used his nipples as eyes, his navel as a mouth, and grasping his shield and battle-axe, he danced.” The headless Xingtian was a monster formed both by a lack of organs and an inversion or misplacement of organs.

*

Eunuchs in the Forbidden City were monsters formed by a lack of organs. Sima Qian was a monster who wrote the Records of the Grand Historian. I was a monster. I’d lost a breast—I too was a monster formed by a lack of organs.

*

Falling out of love with the bathroom was one thing; whether or not I was a monster was another, but regardless, I still had to go into the bathroom every day, and I had to bathe. Sitting in the tub, initially I worried that the wound would break open. In fact, my concerns were unfounded. The wound was stitched perfectly, granulation tissue growing over it. I’d never seen such a tight and seamless zipper. Who was the first surgeon? Whose idea was it to cut open someone’s skin and then stitch it back up? It’s like sewing clothing.

Sewing skin on a person’s body looks similar to sewing clothes, but it’s actually not the same. Only primitive people sewed clothing and stitched up skin in the same manner. Primitive people’s clothing was made from leaves and animal hides. The leaves didn’t necessarily have to be stitched—they could protect the body by being draped around it and hanging down, discarded a couple days later after withering. Animal hides were real clothing and marked the advent of human sewing. Two animal hides, perforated at the edges, were joined together with sinew. Although the two skins were joined together, there were gaps in between, resembling how we lace up sneakers today.

The jade garments stitched with gold thread in ancient times and iron armor for soldiers during the Qin dynasty followed the same method used to sew animal hides, the key difference being that the four corners were linked together, the threads wrapped and fastened. But you can’t sew clothes this way. Clothes can’t have gaps everywhere. You have to sew them tightly so that they’re as strong as a wall, a seamless heavenly robe. The fabric used nowadays is different from animal hide, much softer—even if it’s made from animal hide, it can still be seamless. Fabric can be folded, leaving the fabric edges on the back side. After it’s sewn, the fabric can be flipped over to the front side and ironed smooth and neat. Jade, iron, and hard leather can’t be folded. You have to pierce holes, pull thread through the holes, and close up the seam. It’s the same with skin.

Skin isn’t fabric. It can’t be sewn inside-out. Fortunately, the way God created the human body is beyond amazing. Stitched-up skin has blood vessels and nerves, epidermis and dermis, hair follicles and sweat glands, yet it can regulate its own growth, skin connecting with skin, reuniting in no time. The human body is a true heavenly robe without any seams. The body that undergoes surgery is only left with a scar, totally leakproof. Life is so amazing: half an earthworm can be reborn, a starfish can be perpetually regenerated, chickens can be fitted with duck wings, a pig kidney can be transplanted into a human body.

My friend who loves cats and Peanuts comics and Truffaut films also loves her bathroom. What does she think about when she sits in the bathtub? Stitching things together? Ah, that’s a possibility. The stitching she has in mind certainly has nothing to do with clothing or skin, but film, where stitching becomes splicing. She might think about Jules and Jim, The 400 Blows, Close Encounters of the Third Kind, The Wild Child, and so on. In truth, a film is a flowing jade garment stitched with gold thread, bits and pieces linked together.

A couple decades ago, my friend who loves cats and Peanuts comics and Truffaut films and Mozart’s music and I became obsessed with film splicing. Back then, we used to go to “Studio One” several times a week as though we were taking classes, watching works by Antonioni, Luchino Visconti, Fellini, Godard, Truffaut, Louis Malle, Kurosawa, Mizoguchi Kenji, Kobayashi Masaki, and many other directors unfamiliar to us. After watching and watching, we wanted to make our own experimental films.

This involved scrimping and saving, buying a Super 8 mm camera, buying film, writing a script, and scouting the streets and alleys in search of just the right scenery. The effect of using a handheld camera was that the footage was jerky, constantly shaking, which could only be described as extremely realistic. My friends all shot films, ten to twenty minutes in length. Pleased, they put on an experimental film exhibition. I didn’t go out and shoot a film. In my mind, I compiled a series of dissolving shots—pendulum / cradle / wooden horse / swing—swaying back and forth, but I couldn’t lift the camera. It was too heavy. My dream of editing, directing, and shooting a film vanished.

I may not have shot an experimental film, but that didn’t mean I didn’t conceive of one. A series of shots would appear in my head. The “Odessa Steps” sequence in Eisenstein’s Battleship Potemkin is truly a classic montage; arranging the three lions in a different order would have an entirely different meaning. I pondered questions such as, should a film opt for Renoir’s single-shot mise-en-scène, or Eisenstein’s style of montage editing?

I saved up some money and bought a 16-mm projector and a small splicer. This type of home splicing machine was really small, like a hole puncher, no bigger than a point-and-shoot camera. You could pick up the film and splice it yourself. If you didn’t want a certain section, chop! The little machine was sharp, just like Justice Bao Zheng’s guillotine that chopped the heartless and unfaithful Chen Shimei, quickly and efficiently cutting the film into two sections. Destroying something was the easiest thing; constructing something was the hard part. You had to join two frames of film, but it was a struggle for the little splicing machine. Special glue was applied to the edges of the film, then they were stacked so they overlapped, glued, and pressed tightly. It would seem fine, but during the film screening, suddenly it’d break again. This method of stitching was neither how primitive people sewed animal hides nor how modern people sewed clothing—there were no needles, no perforations, no seams, no threads, only adhesive, close encounters of the third kind indeed. The “work” I submitted to the experimental film exhibition was entirely comprised of discarded footage that I’d spliced together, dozens of pieces in total. During the screening, after a while, the film would break, then it’d be joined back together, and before long, it’d break again. Fortunately, those who attended the film exhibition understood the situation; they were patient and didn’t complain, unlike the midnight moviegoers who sliced up their seats.

My friend who loves cats and Peanuts comics and Truffaut films and Mozart’s music doesn’t necessarily think about movies while lying in the bath. How were the cosmic creatures and humans spliced together in Close Encounters of the Third Kind? Music. There was no need for strings, threads, bones, needles, or glue, and written words didn’t work, either. Modern and ancient people could splice together written symbols, while space creatures relied on acoustic symbols.

Sesame Ball is the cat of my friend who loves cats. Sesame Ball is completely sesame-colored and loves eating plastic bags. My friend always has to take care to hide the plastic bags at home, or they’ll become a delicacy if they come into contact with Sesame Ball. All that chewing—I don’t understand the taste and appeal of plastic bags, eating them to the point of indigestion, then troubling one’s owner to pull them out from the tail end. Sesame Ball is as naughty as a toddler, and my friend treats Sesame Ball like her child.

According to expert research, except for hair and nails, any part of the human body can grow a tumor. In the realm of living things, both plants and animals can develop cancer. Cattle, sheep, dogs, cats, fish, shrimp, insects, turtles—there’s no exception. I don’t know what kind of cancer cats get. Do male cats get intestinal, stomach, liver, or nasopharyngeal cancer? Do female cats get uterine or breast cancer? When a cat develops a malignant tumor, there must be no way to save it—who will perform surgery on a cat to remove it? Are there hospitals for cats to receive radiation therapy?

If Sesame Ball were to get cancer, I don’t know what my friend who loves cats would do. I think she’d probably be the first person to advocate for radiation therapy for cats, or, she might organize an animal cancer prevention society with a friend named Mai who also loves cats, and Mai’s friend Yeung who may love cats, and a bird-loving friend named Wai with whom Yeung and friends often drink Tieguanyin tea, plus a group of people whom they’d ask to join.

I hope that Sesame Ball and my friend who loves cats are happy and healthy, sitting comfortably in a chair and listening to Mozart. Ah, Mozart! The Cultural Center has opened, and the building’s outside appearance seems to be poorly received. People’s criticisms include: it faces the sea but doesn’t have windows, which is a waste of a perfectly good sea view; it’s oddly shaped, and nowhere near grand enough; it lacks Eastern flavor, and there’s no artistic feeling; the color is too pale. My friend who loves cats shared her opinion over the phone. It’s terrible—it looks just like a bathroom. At different times, in different places, we feel differently about the bathroom.

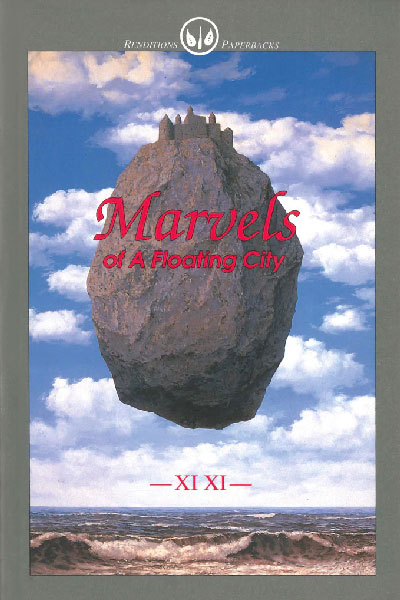

Three Texts by XiXi

Find a list of useful links to websites, databases and scholarly articles related to Xi Xi’s literary works.

Since November 2021, we have organized various writing workshops both online and in person, in areas such as Sham Shui Po, Wan Chai, Kowloon Tong, etc. Learn more about these workshops.

©2025 - All rights Reserved. Our Xi Xi Our City.